The Collapse of Strategy and Its Implications

The Collapse of Strategy and Its Implications

“Strategy” might be one of the most elemental parts of a business. And the most misunderstood.

Perpetuating the problem is the proliferation of corporate strategy groups and “strategy” job titles that involve very little strategy in the economic sense of the term and instead serve either as an umbrella for business activities that fall under no other category―business debris―or as a rubber stamp.

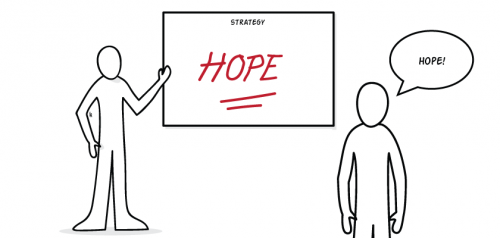

The very word “strategy,” according to Michael Porter, is overused. Sometimes, organisations conflate “strategy” with mission or operational effectiveness. Sometimes, organisations distort “strategy,” making it lopsided, an exclusive view of demand and customer needs. Or sometimes, after adopting an amalgam of competitor initiatives, organisations develop a “strategy” that has the same feel as a jarring cubist painting.

Perhaps the most alarming part is that most organisations believe they have a strategy when in fact they have none. In the book Understanding Michael Porter, The Essential Guide to Competition and Strategy, in an excerpt from an interview with Harvard Business Review’s Joan Magretta, Michael Porter says: “I’d have to say that the worst mistake—and the most common one—is not having a strategy at all. Most executives think they have a strategy when they really don’t, at least not a strategy that meets any kind of rigorous, economically grounded definition.”

“Strategies fail from within,” according to Porter. The entire notion of traditional strategy, one that rigorously assesses unique choices on both the supply and demand side, collapses in many organisations. No strategy means no direction, a plight that accidentally snowballs the number of initiatives a company takes on. “The essence of strategy is about choices,” Porter is known for saying. But if you have no strategy, how can you make strategic choices?

Trade offs and “Initiative Overload”

Organisational choices determine the allocation of resources. And yet. “It sounds simple but many companies cannot do it. There is a fundamental inability to make the right choices,” Porter says.

Making choices is exactly where many organisations falter. It’s not about making right or wrong choices, but about making no choices at all. Initiatives balloon and soon an organisation feels incoherent or overwhelmed. But how, operationally, does this happen?

A recently published Harvard Business Review article, Too Many Projects: How To Deal With Initiative Overload by Rose Hollister and Michael Watkins tackles this very question.

- Impact Blindness: “Many organisations lack mechanisms to identify, measure, and manage the demands that initiatives place on the managers and employees who are expected to do the work.”

- Multiplier Effects: “Because functions and units often set their priorities and launch initiatives in isolation, they may not understand the impact on neighbouring functions and units.”

- Political Logrolling: “I will support your initiatives if you support mine.”

- Unfunded Mandates: “Executive teams often task their organisations with meeting important goals without giving managers and their teams the necessary resources to accomplish them.”

- Band-Aid Initiatives: “When projects are launched to provide limited fixes to significant problems, the result can be a proliferation of initiatives, none of which may adequately deal with root causes.”

- Cost Myopia: “Another partial fix that can exacerbate overload is cutting people without cutting the related work.”

- Initiative Inertia: “Companies often lack the means (and the will) to stop existing initiatives. Sometimes that’s because they have no ‘sunset’ process for determining when to close things down.”

To summarise, Hollister and Watkins write, “What trade offs are we willing to make? In other words, if we do this, what won’t get done?” Choosing trade offs and setting limits are hard. Organisations are often scared to forgo any initiative when a competitor is knee-deep in it. Partly, this can be traced back to human disposition.

“Human nature makes it really hard to make trade offs, or to stick with them. The need for trade offs is a huge barrier. Most managers hate to make trade offs; they hate to accept limits. They’d almost always rather try to serve more customers, offer more features. They can’t resist believing that this will lead to more growth and more profit,” says Porter.

An even more fundamental human hurdle might be found in another psychological study I found buried in the same Harvard Business Review October issue: “People primed to feel busy….typically boosts one’s sense of importance.” People love to feel important regardless of the strategic impact of what they’re working on, e.g., the metastasis of meetings.

Organisations, like people, have a hard time remaining true to the core of who they are especially as distractions and external pressures mount. The lure of initiatives launched by competitors is usually shiny but erroneous. It’s human nature to get caught up in competition.

“When you ask a company, what success looks like, the answer is ‘being the best in my industry’. That is a natural human way to think, but in business competition, that is not the way to think about success. The reason is that there is no [one] best company,” says Porter.

Many organisations have lost sight of this fact. The basis of a successful strategy is, paradoxically, not universal. A successful strategy is idiosyncratic.

Author: Stephanie Denning

Source: https://www.forbes.com/sites/stephaniedenning/2018/10/28/the-collapse-of-strategy-and-its-implications/