Training Employees to be the Eyes and Ears of the Company

Training Employees to be the Eyes and Ears of the Company

By Jen Colletta

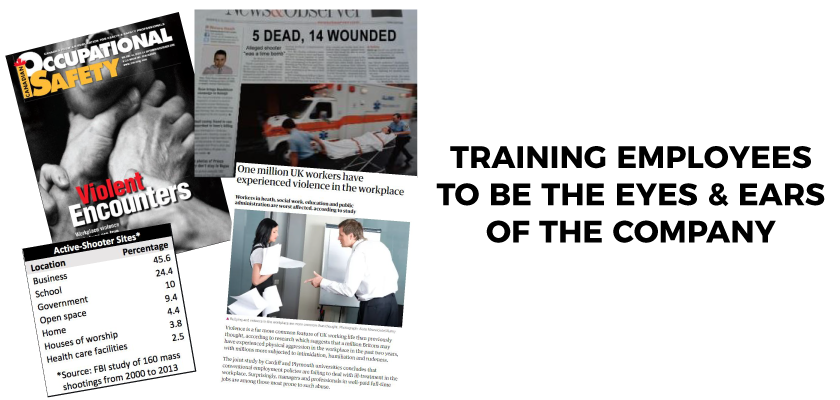

The statistics about workplace violence are alarming: Nearly two million Americans are victims of workplace violence each year — yet a quarter of violent incidents at work go unreported, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. The severity of such incidents varies widely, but the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports workplace homicides jumped from 83 in 2015 to 500 just one year later, with homicides accounting for about 10% of all fatal occupational injuries. That year, nearly 80% of workplace homicides were the result of gun violence.

With workplace shootings occurring with seemingly increasing regularity, many companies are making active-shooter training a grim reality at their workplaces. While such programmes are essential to prepare workers for an emergency situation, there’s a lot more companies should be doing to stymie workplace violence before it escalates, says Matthew Doherty, senior vice president and leader of the Threat and Violence Risk Management Practice at Hillard Heintze.

Doherty joined the security and risk-management firm 12 years ago after a career in the U.S. Secret Service, retiring as the special agent in charge of the National Threat Assessment Center. Now, Doherty and his team advise private-sector organisations and federal agencies on active-shooter planning and threat assessment, with a focus on creating policies and programmes that support a culture in which workforces are empowered to identify and report potential threats.

HRE recently spoke with Doherty about this work and about the integral role HR leaders can play in preventing workplace violence.

Your active-shooter training focuses not just on what to do if someone opens fire, but also how to prevent situations from progressing to that point. How does that compare to most standard active-shooter training today?

Hopefully, it’s the start of a trend. Oftentimes, I’m called by companies because of media exposure around the phenomenon of active shooters in the workplace and asked to provide active-shooter training — and I’ll do it, and do it well. We’ll teach people how to run, hide, fight and how to react if there is a shooter in the workplace. But my first response when I get these calls is, “What are your violence-prevention programmes and policies?” It’s a fact that most active shooters, with very few exceptions, have some association with the company, whether they’re a terminated employee, a suspended employee, a disgruntled customer, an ex-husband of an employee. When you hear the statistic that 33% of women killed in the workplace are killed by an intimate partner, that’s almost to epidemic proportions. So, companies need to be thinking about their policies in general and what managers can do to recognise signs of an issue. There have been behaviours that have concerned others in almost every single [recent high-profile case of workplace violence], so if we can start identifying those behaviours early enough, there is the potential for intervention before the situation escalates into violence.

Are you finding that many of these companies have any policies in place for violence prevention?

Not yet. We do an analysis of violence-prevention policies so we can help them build a programme before we even think about doing training, and we follow best-practice guidelines [for helping companies create such policies] from the Department of Labor, OSHA and Society for Human Resource Management. We’ve found several commonalities that point to not-very-sound approaches to workplace-violence prevention. For example, in most employee handbooks we come across, we find that workplace-violence-prevention policies are punitive in nature, with a focus on zero tolerance: “Workplace violence is not to be tolerated at Company X.” Well, if you think about it, most acts of workplace violence are not committed on impulse; they’re planned in advance, and there are warning signs. If someone is suffering depression or despair, is that a violation of this zero-tolerance policy? If you notice that your female co-worker is wearing what appears to be excessive makeup to hide bruises, how is that a zero-tolerance violation? When I ask for policies, I get these zero-tolerance policies, where companies say how they’ll fight direct threats of bodily harm or sexual harassment. Those, of course, should be in place. I’m fairly confident that if I walked into any workplace and there was a fight between two co-workers in the lobby, it would certainly be reported. But what about the early warning signs of despair, depression, domestic abuse? Those warning signs, left unchecked, can lead to the acts we’ve seen in the news.

What does your training look like?

We target three audiences. The first is the general workforce, who are the eyes and ears of the company. They’re the people you see, after there has been an active-shooter situation, being interviewed about how this person’s behaviour concerned others. That training is typically less than an hour and can be done in person or through an online learning-management system, and it focuses on the behaviour signs to look for and emphasises that reporting warning signs isn’t a punitive approach: If you care about your safety and your co-workers’ safety and well being, it’s not a whistle blowing exercise if you recognise and report warning signs.

We also have a training programme for managers and supervisors to help them understand how to handle different issues that the general workforce may report to them. And the third, and just as important, is for an interdisciplinary team, which the DOL, OSHA and SHRM all recommend. It can be a team of HR folks, legal, security, ad hoc members of the [employee-assistance programme] or local police. If there is somebody whose behaviour is concerning, you can have this interdisciplinary team look at it, instead of just the security director or HR.

Beyond training, what policies can employers put in place to support a violence-prevention strategy?

One that we recommend and that is a best practice is regarding protective or restraining orders. There are a whole host of reasons acts of violence [from intimate partners] take place at workplaces; it could be jealousy, the fact that the workplace is what’s providing this individual independence or simply that’s where the person can be located. So, if you have a restraining order against someone, some companies now have a policy that you have to bring it to the supervisor or to HR, and it will be handled confidentially and sensitively. Here’s why it’s important the company is made aware: People often will get these types of orders in the place where they live, but it isn’t expanded to their workplace, and it may only cover a different police jurisdiction. If you live in one town and work in the next town over, that information won’t be shared with the local police whose jurisdiction includes your workplace, so the employer needs to make sure that police where the workplace is located are aware of this order. You want to get a copy of the order, especially if there is violence involved, and a picture of the person named in the order, and that can be posted at the entrance to the building or at the security station. You can offer the employee an escort to their parking spot because that is often the most vulnerable point at the workplace. And the employee needs to be reminded that they will not be discriminated against — not fired or denied a promotion or treated differently — merely because they are a victim, or suspected of being a victim, of domestic abuse.

What does such a policy look like in practice?

We just recently trained the general workforce of a major insurance company. During the break, the CEO was up at the head table with me and an office manager approached me with a young woman I could tell was distraught; I knew right away she had a restraining order and was coming forward. She was a good employee for four years and was very well-regarded. And she said, “I have a restraining order, and I haven’t had the courage to bring it forward to HR.” The CEO was there with me and there was no judgement. They changed the access controls to the building, provided her a special parking space, got the photo, notified police — and she’s still an employee there. And I think there were other employees there paying attention to how this was handled, who could see, “This company cares about me.”

How can HR help cultivate that type of culture, where people feel comfortable coming forward to identify potential issues?

Without negating any zero-tolerance policies, truly successful violence-prevention programmes need to involve an educated workforce. They need to know about things like protection regarding restraining orders, that warning signs won’t be handled in a punitive way, to identify concerning behaviours — and, for all that to happen, HR has to provide leadership in creating a culture of caring. They need to create an atmosphere where this issue is not treated as a whistle blowing exercise so that the workforce will come forward; if HR just has a strict “We won’t tolerate violence” approach — if that’s the summation of the policies — there will be a reluctance to bring forth concerning information. All of this work needs to promote courtesy, respect and safety. If those three pillars can be promoted by HR, it’ll provide a much safer workplace for everyone.

Author Jen Colletta is managing editor at HRE. She earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in writing from La Salle University in Philadelphia and spent 10 years as a newspaper reporter and editor before joining HRE. She can be reached at hreletters@lrp.com

Source: https://hrexecutive.com/training-employees-to-be-the-eyes-and-ears-of-the-company/